Previously, the most well-known use for such technology involved something you’re probably familiar with if you’ve cashed a check sometime in the last 60 years: Magnetic Ink Character Recognition, or MICR.Īn E-13B font specimen, as shown in a 1995 patent filing. OCR-A wasn’t the first font to tackle these machine-scanning issues, but it was a major step forward in that it was a complete alphabet that was readable by both machines and humans.

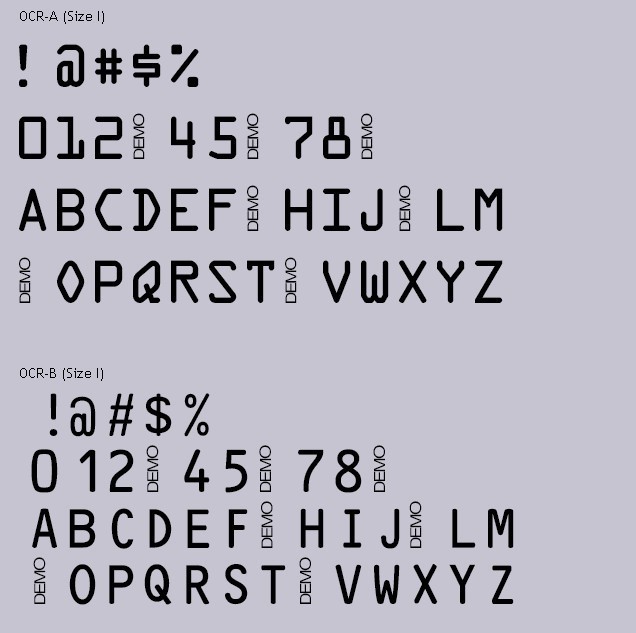

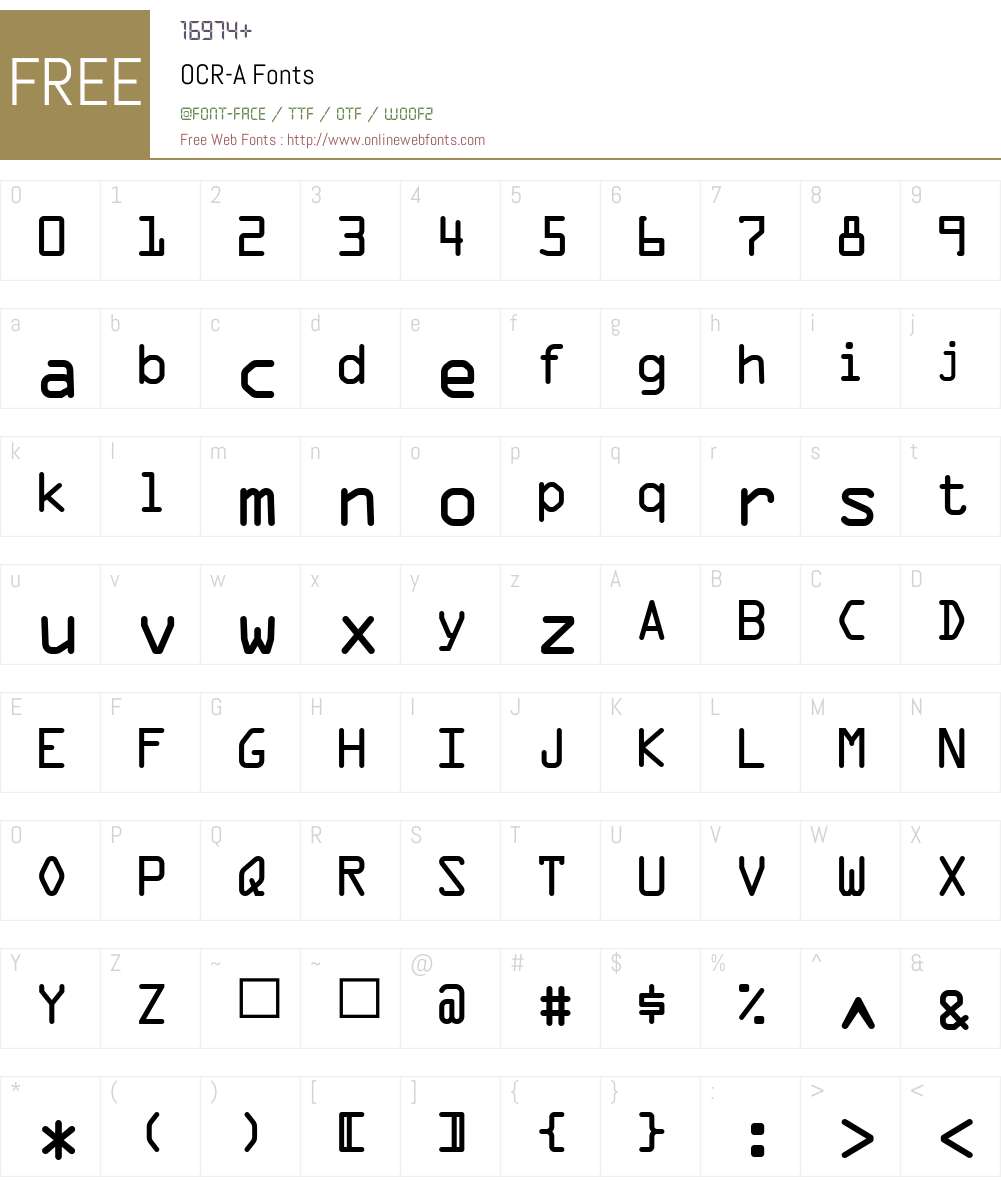

In contrast, typefaces specifically designed for accurate OCR, such as OCR-A and OCR-B fonts, have uniform stroke widths and exaggerated distinctions between similar symbols such as Ο and 0 or 1 and l. Therefore curved strokes may vary in width according to their local orientation. To imitate fine penmanship, vertical strokes are thick compared to horizontal strokes, and NW-SE diagonals are thicker than NE-SW diagonals. Many of the typefaces used today are derived from medieval calligraphy, only slightly modified by the limitations of early printing technologies (wood blocks and moveable type). As the 1999 document Optical Character Recognition: An illustrated guide to the frontier explains: (We’ll overlook the fact that the foundry is responsible for Hobo.)īut just one of its fonts has a spot in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, and that font is OCR-A, a typeface created in 1966 to be read for a very specific audience: machines.Īnd the machines of the time did not have the ability to differentiate between fonts, making such a font necessary. Franklin Gothic, Century Schoolbook? Both of them credited to ATF typographers. for decades, has a lot of fonts to its name, many of them incredibly well known and of high-quality.

( Eric Fischer/Flickr) How the challenges of making fonts readable by machines influenced typographyĪmerican Type Founders, trust of 23 different type foundries that defined typography in the U.S. The OCR-A typeface, shown at the Museum of Modern Art.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)